Item: in the 1950s research was starting to suggest smoking cigarettes might be bad for you, so one company beefed up their filter with asbestos

got nostalgic for being a camp counselor at a horse camp, i guess??

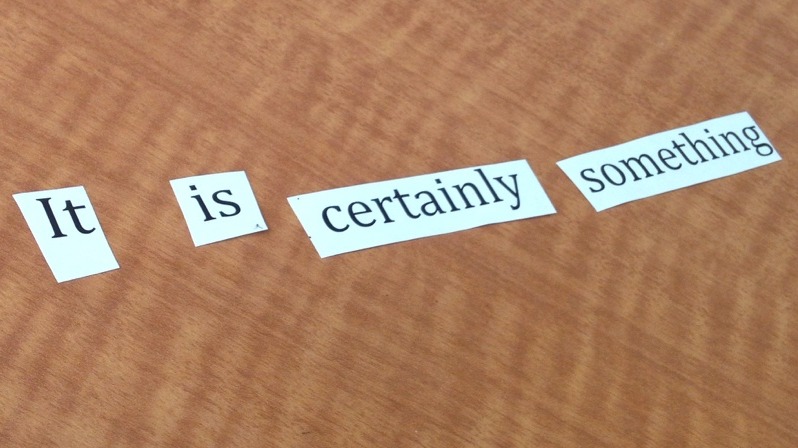

Blackout Poem Made of Disability Benefits Applications and Denial Letters:

[Image ID: A blackout poem. The edges of the black are straight and rectilinear. I will indicate breaks in the line using the slash symbol /. Some of the excerpts include boxes where you could draw a check mark. I will indicate these by writing (box). The poem goes

Answer every question. / Please tell us if you want us to return them to you. / Select the heaviest weight lifted. / Using fingers to touch, / (Box) One hand (Box) Both hands / Using hands to seize, (Box) One hand (Box) Both hands / reduction / refusal / Termination / Penalty / You can give us more facts to add to your file. / You do not meet with the person who decides your case. / Notice of Decision — Unfavorable / Disabled worker’s name / Date given when disability began / Date of death. /end ID]

The final three lines are from denial of benefits paperwork for workers who died before the end of the mandatory five month waiting period. How many of those deaths are connected to poverty? I don't know, but I can guess.

fanfiction obviously reflects all different kinds of personal fantasies but currently the most amusing subset of these to me are the ones that attach a character's romantic fitness to their managerial proficiency. true 'aging userbase' moment to be like "yes but what if good managers existed, can you imagine"

i am gall; i am heartburn

ah woe my life is full of joy

no love at all for t*mothy sn*der but there are a bunch of library types posting that "do not obey in advance" screencap & i think it is good advice & addresses the extremely common phenomenon of "quiet censorship" or automatic capitulation that a bunch of libraries participate in. it's just also funny to me to act like this will be a new problem? the library that i work for now is run by people who are proud of their professional uprightness & has a board-approved policy against censorship but also treats all people under 18 as the property of their parents & age-restricts AV materials. oh?

first full shift at my new part-time job and i said my partner liked [book] and the person training me assumed immediately that my partner is a man. i am disproportionately upset by this, not least because it is not true

pointing out that capitalist welfare states are built on imperialist superprofits gets a lot of wank on here so just wanted to point to a new example. novo nordisk, denmark's (our favourite nordic model state) largest company (its market capitalisation exceeds the size of denmark's economy) is a pharmaceutical company that saw its fortunes rise after the decades long battle that enforced international IP law on India to prevent it from re-engineering drugs as generics. quite literally extraction of super profits via enforcement of fake monopolies.

From the first article, which is more about the whole industry

Vivas To Those Who Have Failed: The Paterson Silk Strike, 1913

Vivas to those who have fail'd! And to those whose war-vessels sank in the sea! And to those themselves who sank in the sea! And to all generals that lost engagements, and all overcome heroes! And the numberless unknown heroes equal to the greatest heroes known! —Walt Whitman

I. The Red Flag

The newspapers said the strikers would hoist

the red flag of anarchy over the silk mills

of Paterson. At the strike meeting, a dyers' helper

from Naples rose as if from the steam of his labor,

lifted up his hand and said here is the red flag:

brightly stained with dye for the silk of bow ties

and scarves, the skin and fingernails boiled away

for six dollars a week in the dye house.

He sat down without another word, sank back

into the fumes, name and face rubbed off

by oblivion's thumb like a Roman coin

from the earth of his birthplace dug up

after a thousand years, as the strikers

shouted the only praise he would ever hear.

II. The River Floods the Avenue

He was the other Valentino, not the romantic sheik

and bullfighter of silent movie palaces who died too young,

but the Valentino standing on his stoop to watch detectives

hired by the company bully strikebreakers onto a trolley

and a chorus of strikers bellowing the banned word scab.

He was not a striker or a scab, but the bullet fired to scatter

the crowd pulled the cork in the wine barrel of Valentino's back.

His body, pale as the wings of a moth, lay beside his big-bellied wife.

Two white-veiled horses pulled the carriage to the cemetery.

Twenty thousand strikers walked behind the hearse, flooding

the avenue like the river that lit up the mills, surging around

the tombstones. Blood for blood, cried Tresca: at this signal,

thousands of hands dropped red carnations and ribbons

into the grave, till the coffin evaporated in a red sea.

III. The Insects in the Soup

Reed was a Harvard man. He wrote for the New York magazines.

Big Bill, the organizer, fixed his good eye on Reed and told him

of the strike. He stood on a tenement porch across from the mill

to escape the rain and listen to the weavers. The bluecoats

told him to move on. The Harvard man asked for a name to go

with the number on the badge, and the cops tried to unscrew

his arms from their sockets. When the judge asked his business,

Reed said: Poet. The judge said: Twenty days in the county jail.

Reed was a Harvard man. He taught the strikers Harvard songs,

the tunes to sing with rebel words at the gates of the mill. The strikers

taught him how to spot the insects in the soup, speaking in tongues

the gospel of One Big Union and the eight-hour day, cramming the jail

till the weary jailers had to unlock the doors. Reed would write:

There's war in Paterson. After it was over, he rode with Pancho Villa.

IV. The Little Agitator

The cops on horseback charged into the picket line.

The weavers raised their hands across their faces,

hands that knew the loom as their fathers' hands

knew the loom, and the billy clubs broke their fingers.

Hannah was seventeen, the captain of the picket line,

the Joan of Arc of the Silk Strike. The prosecutor called her

a little agitator. Shame, said the judge; if she picketed again,

he would ship her to the State Home for Girls in Trenton.

Hannah left the courthouse to picket the mill. She chased

a strikebreaker down the street, yelling in Yidish the word

for shame. Back in court, she hissed at the judge's sentence

of another striker. Hannah got twenty days in jail for hissing.

She sang all the way to jail. After the strike came the blacklist,

the counter at her husband's candy store, the words for shame.

V. Vivas to Those Who Have Failed

Strikers without shoes lose strikes. Twenty years after the weavers

and dyers' helpers returned hollow-eyed to the loom and the steam,

Mazziotti led the other silk mill workers marching down the avenue

in Paterson, singing the old union songs for five cents more an hour.

Once again the nightsticks cracked cheekbones like teacups.

Mazziotti pressed both hands to his head, squeezing red ribbons

from his scalp. There would be no buffalo nickel for an hour's work

at the mill, for the silk of bow ties and scarves. Skull remembered wood.

The brain thrown against the wall of the skull remembered too:

the Sons of Italy, the Workmen's Circle, Local 152, Industrial

Workers of the World, one-eyed Big Bill and Flynn the Rebel Girl

speaking in tongues to thousands the prophecy of an eight-hour day.

Mazziotti's son would become a doctor, his daughter a poet.

Vivas to those who have failed: for they become the river.

-Martín Espada, copyright 2015

Three Swans in Flight by David Lloyd Evans

Accounting is rarely considered the stuff of socialist revolutions, but the case of socialist Tanzania shows how decolonizing the economy quite literally boiled down to correctly calculating prices. At a moment when price controls, inflation, and even nationalization are again at the forefront of public debate, the history of Tanzania’s bank nationalization demonstrates why the arcane technicalities of valuation should not be left to managerial elites alone. Today, advocacy groups like Groundwork Collaborative have made corporate pricing decisions a political issue, and economists like Isabella Weber are exploring how systematically significant prices might be calculated and regulated.

18 September 2024

What is a bank worth? Barclays initially proposed a compensation of nearly £2.5 million. It arrived at the bulk of this figure by projecting past annual profits forward in perpetuity—in particular, by averaging the past two years of profit and dividing that number by an estimate of the so-called capitalization rate (“cap rate”), a valuation technique most often used in real estate.

Barclays argued this was the proper and uncontroversial method for assessing the bank’s present value, equivalent to what a “willing buyer” would offer a “willing seller” in an acquisition and “well understood and accepted in business circles throughout the world.” In the bank’s depiction, such accounting methods were apolitical tools that produced objective facts. The bankers also knew the cap rate valuation did Tanzania no favors. By insisting the formula set the price, they tried to immunize their claims against accusations of self-interest.

The country’s negotiators dissented. On what basis could past profits be presumed to continue indefinitely into the future, and how many years of profits should be averaged to account for the past? Barclays chose two years because they had been especially lucrative, but the Tanzanians insisted that such opportunistic enumerations be amended. At best, they argued, the cap rate technique was a rule of thumb. Rather than imbuing it with objectivity, they rightly saw the calculations as political, reminding Barclays that its prior profits were facilitated by the colonial “cartel” agreement that allowed banks to “impose on the public what charges it liked.” Moreover, the idea that a compulsory nationalization should be judged by the standard of a market transaction belied the categorical difference: there was no “willing” buyer or seller in the 1967 expropriation.

Tanzania suggested that what it owed all nine nationalized banks, including Barclays, amounted to £900,000. Instead of using the cap rate method, government negotiators relied on a protocol called “net asset value.” Also known as “book value,” this approach uses the balance sheet of a business to subtract liabilities from assets. Within a matter of months, Tanzania made deals with most of the affected banks, but the big three balked at this approach and refused to fully open their books (perhaps to avoid revealing a history of tax avoidance).

The 1967 nationalization law had made net asset value the law of the land, and the country could honestly say it was a common enough accounting standard around the world. But Barclays held very few assets in Tanzania, in part due to continually exporting profits to London, and by some accounts its assets were actually less than its liabilities. It thus rightly fretted that “compensation received on a net asset basis will be small,” limited to items like furniture, vehicles, and stationary. As the bank’s chairman put it, “this meant that our 50 years of development and profitable operations were virtually valueless from the point of view of compensation.”

Barclays hoped to use financial accounting as an inviolable law of value, but Tanzania’s insistence turned the presumed fixity of accounting into a proliferation of discretionary choices. Instead of using either cap rate or book value, Barclays proposed they simply multiply an average of past profits by some fixed number of years. Yet how many years of prior profit should be averaged, and exactly how many years into the future should those historical numbers be expected to prevail? Any formula seemed to contain controversial variables.

...

Among the most significant such moves are the investment treaties that move compensation claims out of national jurisdiction and into international arbitration panels. Since 1966, the World Bank has taken the leading role in promoting and overseeing this form of parallel justice, in the process sidelining what might have been more equitable alternatives like investor insurance. By the 1980s, the World Bank and International Monetary Fund were demanding acquiescence to international arbitration as part of structural adjustment programs. Legal scholar Nicolás Perrone reports that over 1,500 international investment treaties were signed in the heady days of capitalist globalization: four per day between 1994 and 1996. This regime of so-called investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) emerged from the frustrations of expropriated banks, oil companies, and other multinationals. Today, it works to further their interests and constrain national sovereignty.

During the Barclays negotiations in Tanzania, domestic law prevailed over international law—most notably in grounding the government’s use of net asset value—and both political and ethical arguments shaped how accounting was used. In contrast, international arbitration now heightens the influence of financial models and limits the latitude of national governments by expanding the types of behavior that triggers compensation. Even legitimate regulation, such as legislating the phaseout of coal power plants or some types of taxation, might be seen as “indirect expropriation” or a violation of the obligation of “fair and equitable treatment.” The arbitration tribunals are staffed by technocrats who are meant to be independent, but in practice their work protects investors (especially in extractive industries).

One way it does so is through the promotion of certain valuation techniques, which have wildly inflated the cost governments must pay for nationalizations. The amounts awarded in recent years have been staggering: $5.8 billion against Pakistan and $8.7 billion against Venezuela in 2019, for instance. Instead of funding schools or hospitals, Pakistan pays foreign mining companies (including Canada’s Barrick Gold) and Venezuela owes oil extractors (like Houston’s ConocoPhillips).

Legal scholar Toni Marzal has detailed this rise of a theory of compensation that is equal parts peculiar and aggressive. Since the 1990s, arbitration tribunals have not only come to embrace the belief that compensation must be full and at the “fair market value.” They also now insist on establishing this value through a financial model known as “discounted cash flow” (DCF), which totally ignores mitigating factors—such as historical harms, or a government’s ability to pay, or next year’s shift in interest rates. Despite the patina of objectivity, DCF accounting is riven by uncertainties and artifice. While it claims to replicate what an expropriated business would sell for in a real market, its models do not capture the risks, volatility, and imperfections of the real world. In some cases, the compensation paid is more money than the business could sell for in a private transaction. In Pakistan, the enormous sum was awarded to a mining consortium, Tethyan Copper, even though it had not yet obtained necessary authorization, let alone begun operations.

...

What does this merger of law and accounting mean for politics? Doganova argues that discounting’s significance lies less in the truth value of accounting than the specific consequences of a calculation being deemed persuasive. After all, financial practitioners are among the most alert to the basic uncertainty surrounding the value of a new drug or factory; it is partly because of this uncertainty that future revenue is discounted in the present. What really matters, in other words, is not so much that the formula produces “truth.” What financiers want is for the formula to be accepted. We should therefore see financial arithmetic as something like an act of rhetoric: marshaling certain evidence for the means of argumentation and persuasion. When two companies deploy various valuation methods in a commercial acquisition, with their accounts open as part of due diligence, both sides know there is no ironclad set of variables and formulas that would yield an uncontroversial price. Compelled by this result or that, they negotiate before being persuaded and coming to a deal.

The trouble arises when discounting methodologies are deployed with political consequences without inviting the public to the negotiating table. As a style of argumentation, this is a far cry from an ideal of public deliberation, where public opinion and moral values work to legitimate state action. Today, the use of discounting interferes with public reasoning, short-circuiting democratic governance. The privatization of so much of political consequence means that accounting decisions with wider importance never reach the public arena. Drug discovery is a case in point: when pharmaceutical executives decide to invest in profitable interventions for the wealthy, they sacrifice the health of the global poor. Pharma executives may not be fooled by the ultimately speculative nature of the formulas they use, but guided by discounted cash flows—and not the right to health or global justice—their own persuasion undermines public purpose.

Even in cases where democratic mechanisms are ostensibly at play, the resort to accounting can obscure just how arbitrary the formulas are. Pseudo-objective valuation techniques not only establish worth; they justify it. In concert with what Elizabeth Popp Berman calls the “economic style of reasoning,” discounting turns questions of justice into calculations of costs. Climate change is perhaps the preeminent example, where the use of questionable discount rates has encouraged policymakers to underplay the contemporary costs of spewing carbon—part of what Geoff Mann dubs the “new denialism.”

“Remota itaque iustitia quid sunt regna nisi magna latrocinia? quia et latrocinia quid sunt nisi parva regna?”

—

St. Augustine, De Civitate Dei, 4.4

“And so, justice removed, what are kingdoms if not great robberies? And what are robberies if not small kingdoms?”

(via girderednerve)

for my purposes, please consider durable/longterm policy changes, and use whatever definition of the 'gold standard' makes the most sense to you

thank you to everyone who voted! explanation/potted history of american money below cut